This hasn’t always been the way though, as the recently discovered first underwater moving image recording proves – and it’s not all down to the lack of colour, either.

Discover our latest podcast

J.E. Williamson’s Terrors of the Deep is the earliest surviving underwater motion picture recording, and believed to be the first underwater film ever. Having been lost for decades, it was recently recovered by Popular Science’s senior video producer.

Braving the waves

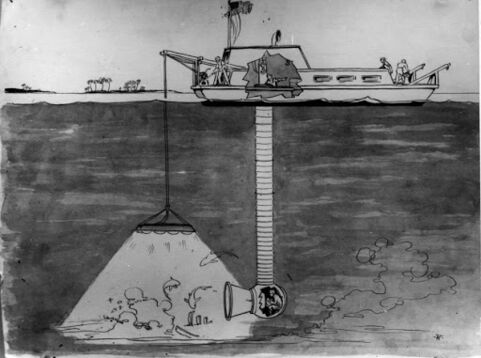

Williamson’s father was a sea captain, and clearly must have instilled an affinity for the sea in his son. The captain built a device that enabled Williamson to see the depths of the sea – an interlocking iron tube with a small viewing chamber.

This device was the basis for Williamson’s 1914 invention, named ‘the photosphere’. By adding a larger, windowed viewing chamber and lights to the tube, he was able to take his camera down under the waves with him.

It wasn’t long before Williamson dedicated his efforts to making his dream come true: shooting a fully-fledged motion picture under the sea.

Man vs shark

Williamson had the camera, the photosphere, and access to a boat – the only thing missing was money to fund the film. Luckily for him, he managed to raise the interest of a few sponsors – unluckily for a certain horse and shark, they weren’t after a mellow documentary.

To get the money for filming, Williamson promised his investors footage of the ultimate battle:man vs shark. Considering these were still the early days of filmmaking, you have to hand it to him: he wasn’t afraid to raise the stakes.

The idea clearly didn’t sound as insane to the money people as it does now, so Williamson got his funding and set about planning his film.

Terrors of the Deep

Having made his preparations, Williamson boarded the barge aptly-named Jules Verne and set out for the Bahamas to make the first underwater film a reality. The promised man vs shark encounter naturally required a live shark – and getting a live shark to turn up required not-so-alive bait.

To lure in a shark, Williamson and his crew deposited a dead horse in the water, hoping it’ll get the attention of some deep-sea predators. He wasn’t mistaken: soon, a shark appeared. The hour-long film, then, involves rather harrowing images of a dead horse floating near the water’s surface.

With the appearance of a shark, Williamson – lying in wait as his camera was rolling, capturing the whole thing – struck. One thing we certainly can’t question is the man’s dedication – he literally came at a hungry shark with nothing but a knife.

Grabbing the shark’s fin, he positioned himself beneath the animal – executing his plan of stabbing its belly. He later described the whole thing in his memoir, noting that

‘A quivering thrill raced up my arm as I felt the blade bury itself to the hilt in the flesh…Then a blur, confusion—chaos.’

The film was originally named Thirty Leagues Under the Sea, but we can all probably agree that Terrors of the Deep is a much more fitting title.

Shocking violence

Williamson’s film is harrowing to watch – it’s tough to pinpoint whether it’s the image of the dead horse or that of the shark’s death that’s more disturbing to watch. As unethical as we’d find his method and his footage by today’s standards, though, it can’t be denied that Williamson’s device and ideas were innovative, ingenious, and just a little bit insane. He literally risked his life to make the first underwater film.

It’s interesting to wonder whether the film would have looked the same had Williamson been able to secure the funding without the need for thrilling, frightening footage. As it was, however, Williamson was willing to do anything to make his film, and he couldn’t do so without money.

Even today, over a hundred years since Williamson attacked a shark on camera, most filmmakers will likely agree that the general trend among investors hasn’t changed much. There’s a reason why we don’t regularly see peaceful documentaries in cinemas and why screenwriters and directors often need to adapt their work to meet their investors' expectations: sex and violence are what sells, and judging by Williamson’s experience, at least half of that statements has always been true.