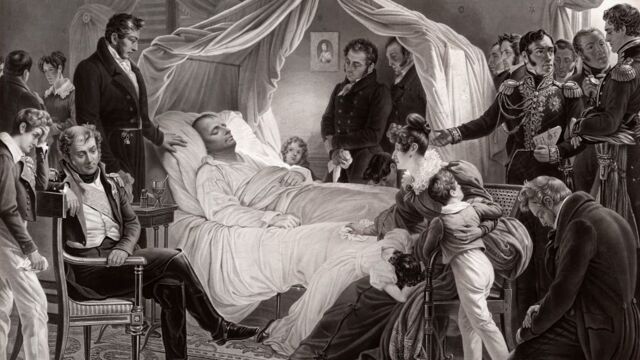

In the spring and throughout the summer, the Army Museum in Paris will be presenting an exhibition entitled ‘Napoleon Is No More,’ to commemorate the two centuries since the death of the emperor Napoleon. Napoleon's death occurred on May 5th, 1821 on the island of St Helena in the middle of the South Atlantic. It was there that the British and their allies forced the emperor into exile following the bitter French defeat at the Battle of Waterloo.

Discover our latest podcast

It was not until two months later that Europe was informed of Napoleon's death. From then on, rumours circulated about the cause of death. Thierry Lentz, a historian specialising in the First Empire, director of the Napoleon Foundation, which is co-organising the exhibition, and co-author of The Death of Napoleon: Myths, Legends, and Mysteries (published by Perrin), looks back at these often far-fetched theories and sets the record straight.

What Napoleon’s autopsy says

‘Napoleon died in excruciating pain,’ the historian summarises. Ten days before his death, he finished dictating his will and declared: ‘Wouldn't it be a pity not to die after having put one’s affairs in such good order?’ He then suffered from increasingly violent abdominal pains. ‘Napoleon was very weak and anaemic,’ describes Thierry Lentz. ‘His father died in similar circumstances, probably of a tumour in the stomach area. Convinced that he was going to die of the same thing, the emperor asked for his body to be autopsied so that his son, L'Aiglon, could be informed,’ who was in Europe.

The autopsy, carried out by the French doctor Dr Antommarchi, is ‘perfectly readable by today's doctors,’ says Thierry Lentz. It shows that the emperor had a perforated stomach ulcer. ‘Normally, people die immediately, but Napoleon was lucky: his liver plugged the hole,’ Thierry Lentz continues.

The autopsy also revealed stomach lesions, probably cancerous, as well as bloody lesions. To make matters worse, the remedy the emperor was given at the time aggravated the bleeding. ‘Two or three days before his death, a mercury-based medicine was administered to him,’ says Thierry Lentz. ‘At the time, it was not known that this was harmful to health. This overdose certainly caused a massive haemorrhage.’

The theory of poisoning

Despite these numerous diagnoses, one theory continues to excite conspiracy theorists: that of arsenic poisoning. ‘It appeared in the 1960s following an improper reading of the Memoirs of Napoleon's valet,’ explains Thierry Lentz. A Swedish stomatologist, convinced that he recognised the description of the symptoms of poisoning, had analyses carried out on the emperor's hair, which revealed traces of arsenic.

‘In the 19th century, it was customary to give oneself hair curls,’ recalls Thierry Lentz. Analyses were carried out on locks of Napoleon's hair at various stages of his life, as well as on the hair of his mother, his sisters, and his son. All of them revealed similar doses of arsenic. The theory is also based on a rumour concerning adultery: Napoleon was allegedly having an affair with Albine, the wife of the Count of Montholon, his closest adviser. ‘In reality, his wife Albine had left a long time ago,’ laughs Thierry Lentz. ‘The renowned forensic scientist Philippe Charlier started all the studies from scratch. The re-reading of the documents shatters the theory of poisoning.’

‘There is another theory that borders on the ridiculous,’ adds Thierry Lentz. ‘It's that of the substitution of corpses.’ Rumours claim that Napoleon's remains were recovered by the British, and that it is the body of one of the valets that was inhumed at the Invalides in Paris, dressed as Napoleon. ‘It's all a big farce, there's no documentation, but the plot has lasted through the ages,’ says the historian. Certainly, these mysteries, which have been maintained for two centuries, continue to fuel the Napoleonic legend.