A fever, cough, breathing difficulties, a tight chest, loss of taste and smell… The more research progresses, the more we are realising that COVID-19 symptoms come in many different forms. In New York, for example, doctors treating patients with the new coronavirus have also observed other symptoms that, until recently, there had been very little mention of. Some patients are said to be experiencing confusion, to such an extent in fact that they don’t know where they are or what year it is.

Discover our latest podcast

Seizures and strokes

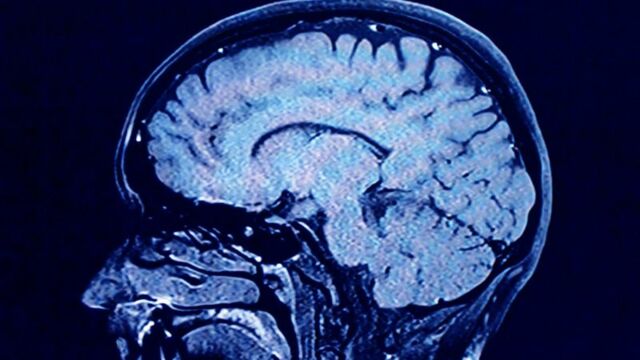

Although this loss of awareness can be a consequence of low oxygen levels in the blood which, in turn, means not enough is being transported to the brain (20% of oxygen consumption in the body for just 2% its total weight), the confusion observed in some patients appears disproportionate in comparison to the state of their lungs, and so rules out this hypothesis.

But this raises the question of whether the coronavirus can affect the brain and the nervous system. According to one of the first studies on the subject which was published in the journal of the American Medicine Association (Jama), doctors reported that 36% of 214 Chinese patients showed neurological symptoms ranging from a loss of smell and nerve pain to seizures and strokes.

In the New England Journal of Medicine, doctors from Strasbourg explained that more than half of the 58 ICU patients they were observing were confused or agitated and scans of their brains revealed possible inflammation.

‘Overactive' immune response

‘If you become confused, if you’re having problems thinking, those are reasons to seek medical attention,’ explained S. Andrew Josephson, chair of the neurology department at the University of California, San Francisco, to AFP.

The virus can affect the brain in two different ways, as Michael Toledano, a neurologist at the Mayo Clinic in Minnesota, recently explained. First of all, by triggering an abnormal immune response known as a ‘cytokine storm’, which causes inflammation in the brain (autoimmune encephalitis) or secondly, by directly infecting the brain (viral encephalitis).

The most likely assumption based on current evidence is that the virus causes an ‘overactive immune response’ rather than brain invasion. But to be sure, researchers would need to detect the virus in the cerebrospinal fluid, which has only previously been documented once in a 24-year-old Japanese man, whose case was later published in the International Journal of Infectious Disease. Imaging showed that his brain had become inflamed, but the test was never validated and scientists remain cautious.

40% of cured patients end up consulting a neurologist

Jennifer Frontera, neurologist at Langone University Hospital in Brooklyn, is part of an international research project to standardise data collection. Her team has already documented cases of seizures in COVID-19 patients who had never experienced them prior to falling ill, and have also observed tiny brain haemorrhages that they have described as ‘unique’.

‘We're seeing a lot of consults of patients presenting in confusional states,’ explained Rohan Arora, neurologist at Long Island Jewish Forest Hills Hospital, to AFP. He claims that 40% of recovered COVID-19 patients end up consulting neurologists. However, it seems returning to normal is taking longer than for people who have suffered a heart attack or a stroke.