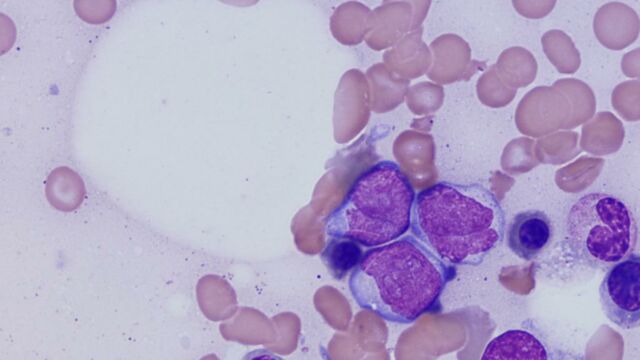

Multiple myeloma, otherwise known as Kahler's disease is a rare disease in the category of blood cell cancers (haemopathy) and non-Hodgkin's lymphomas, i.e., bone marrow cancers. In fact, this substance present in certain bones is the origin of blood cells. White blood cells called plasma cells (or B-lymphocytes) develop there. Their function is to produce antibodies (immunoglobulins), which defend the body against infection.

Discover our latest podcast

However, for unknown reasons and in multiple myeloma, these plasma cells start to proliferate excessively and at the same time attack the surrounding bone and bone marrow. They also produce only one monoclonal antibody, the ‘M’ protein, which leads to a decrease in the production of other immune proteins. These effects have serious health consequences.

Multiple myeloma is a complex cancer that may require management over several years. In most cases, there are several phases of remission and relapse, requiring different treatments. Except in the case of localised plasma cell proliferation, Kahler's disease remains incurable. Life expectancy is on average five to eight years after diagnosis.

What are the symptoms of multiple myeloma?

The appearance of multiple myeloma is usually related to the degree of progression. Initially, the disease does not necessarily produce clinical signs, so it is often discovered by chance. However, as the disease progresses, it primarily leads to increasingly severe bone pain in the back (especially the vertebrae), ribs, neck, and pelvis. It can also manifest itself through:

- Hypercalcemia (an increase in the level of calcium in the blood), which can lead to kidney failure, resulting in loss of appetite, thirst, nausea, and vomiting, oedema (swelling), abnormally low or high urine production, or drowsiness;

- Anaemia, causing fatigue;

- A fragility of the bones, facilitating small fractures called ‘pathological’ fractures;

- Prolonged bleeding time from small wounds, responsible for abnormal discharge from the nose or gums;

- The formation of bruises;

- Repeated infections, particularly of the respiratory and urinary tracts.

What are the causes and factors?

The causes of the development of Kahler's disease are still unknown. Only accidental exposure to high doses of ionising radiation is strongly suspected. More recently, American researchers have pointed to the chronic stimulation of the immune system by certain lipids in the blood. But this is still only one lead. Also, in the vast majority of cases of myeloma, there is no family history.

How is it diagnosed?

These significant symptoms point the medical professional towards the trail of multiple myeloma. Biological examinations are then carried out, including protein electrophoresis, to detect a peak in monoclonal antibodies, which indicate a dysfunction of the plasma cells. A myelogram then confirms the final diagnosis. Finally, imaging examinations (X-ray, MRI) may be carried out to detect any bone damage.

How is multiple myeloma treated?

Multiple myeloma detected early does not necessarily require treatment. If the myeloma is asymptomatic (indolent myeloma), regular blood, urine, and X-ray tests may be enough to actively monitor its progress. If there is any sign of disease progression, a multidisciplinary consultation meeting (MDC) will bring together more specialists (radiologists, haematologists, psychologists) to determine the appropriate course of action.

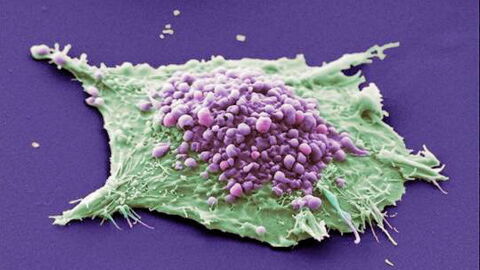

Treatment depends on the patient's age and state of health, as well as the stage and aggressiveness of the cancer. Most often, it combines drug solutions such as chemotherapy (melphalan and cyclophosphamide) and autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (mainly in people under 65 years of age), to regenerate bone marrow attacked by the chemicals. These treatments have significantly improved the patients' chances of survival.

Complications from multiple myeloma (hypercalcaemia, kidney failure, anaemia, bone damage, infections) must also be treated and prevented. They are also often medical emergencies that must be treated as quickly as possible, even before the disease itself. Finally, new targeted therapies (proteasome inhibitors, immunotherapy) are being evaluated, particularly to limit the risk of relapse.