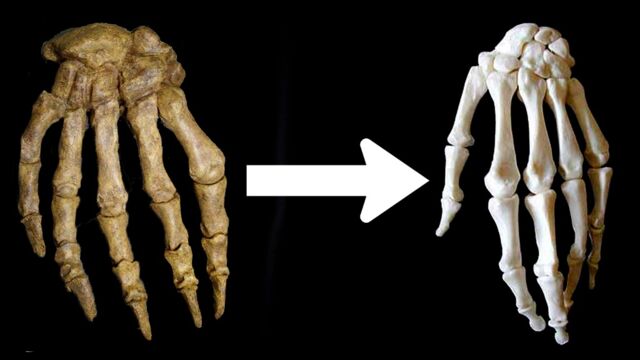

Among the many traits that the human body has acquired through evolution, the hands are probably the most developed organs. These tools, that are unique in the animal kingdom, not only make us different from other mammals but also our primate cousins.

Discover our latest podcast

In comparison to the hands of primates, human hands have a longer and stronger thumb. The other fingers are also shorter, and the wrist is more flexible, while the articular surface is bigger. Although our ability to grip is weaker, our dexterity is outstanding. But how have our hands evolved? This is the mystery that has intrigued specialists for a long time.

Today, a group of anthropologists has come up with the strange hypothesis that this evolution could have been caused by the bone marrow that our ancestors were fond of, as well as producing flint chips.

From the importance of food

Researchers have thought for a long time that using tools to hunt contributed to the evolution of the human hand. But as well as hunting, other activities, especially food-related ones, could also have had an impact on how they developed. Once an animal died, our ancestors used to have to skin and slice the meat and even break its bones to get at the fatty and nourishing bone marrow.

‘These behaviours all involve different materials, different end goals, and different patterns of force and motion for the upper limb [from the shoulder to the fingers],’ explain the researchers at the University of Kent and Chatham in their study, published in June in the Journal of Human Evolution.

Therefore, it is unlikely that each behaviour exerted equal influence on the evolution of the modern human hand.

Multifactorial evolution

Rather, according to the team, the pressure exerted, the relationship between the hand and the tool, the benefits and the time spent doing these various tasks, together conditioned certain characteristics to develop. In order to test the influence of each of these factors, researchers used a manual pressure sensor called Pliance that they gave to 39 test subjects.

Participants then had to perform various Plio-Pleistocene tasks, such as opening nuts, breaking bones by using stone hammers, hammering flint with a stone to produce flakes, using an axe as well as creating shards of rock to be used as arrowheads and even knives. Producing flint-flakes as well as breaking bones to get the marrow out proved to be the most demanding in terms of pressure on the subjects’ hands.

Something to explore

Therefore, it is possible that these repeated activities influenced the evolution of the modern human hand, but many things are still to be kept in mind. It is possible that our ancestors used their hands in a different way to how we do today. Nowadays, we are becoming less and less used to doing manual labour, which can have a big impact on the way we use tools from the past. Moreover, there are numerous other factors that could come into play in this development and further research is necessary to gain a better understanding of this.

Nevertheless, this study provides a solid and interesting foundation for a better understanding of our past and the present that came from it. The team concluded:

When magnitude is taken into account, analyses of the digits as a group, of individual digits and phalanges point to hammerstone use during marrow acquisition and flake production as the best candidates […] that may have exerted primary selective pressures on the evolution of the human digits.