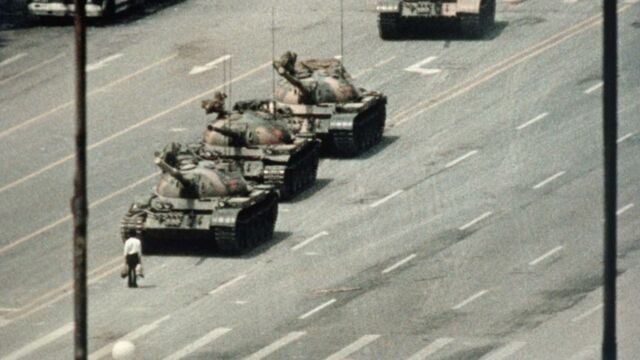

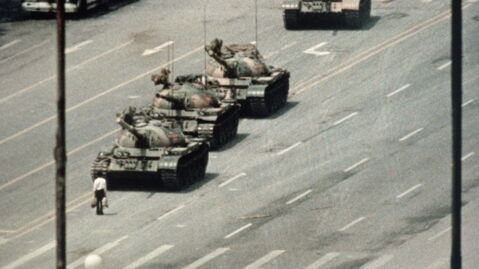

For most people, the only image of the events of Tiananmen is that of an unknown man standing alone facing the tanks. Neither the identity nor the fate of this man is known, but this image preserves the memory of the terrible decisions taken by the Chinese leadership just thirty years ago.

Discover our latest podcast

Student hopes for change

On 4 June 1989, after several weeks of demonstrations in the heart of the Chinese capital, in front of the Forbidden City, the authorities chose to put a brutal end to several weeks of non-violent rallies. These had mobilised a large number of students but also a growing section of the population, particularly workers. Beyond that, the protest had also been echoed in the provinces, in other Chinese cities, reinforcing the authorities' concerns.

Another cause for concern for the Chinese authorities: at the height of the occupation of the square, Mikhail Gorbachev's historic visit to Beijing was taking place, the first such visit by a Soviet leader for over twenty years. The USSR had then entered a process of openness and transparency that would lead to the collapse of the 'fatherland of socialism' just a few months later. Seizing this opportunity as well as that of the massive presence of foreign journalists, the students based their demands on the example of what was happening in Moscow.

Of all options, only massacre was chosen

However, the choice of violent repression was not immediately taken. There were debates within the government. Zhao Ziyang, then General Secretary of the Chinese Communist Party, went to the scene on 19 May 1989 to talk to the students and express his support and that of the factions most open to political change. He was deposed a few days later and ended his days under house arrest in Beijing in 2005.

By contrast, Premier Li Peng and Deng Xiaoping, Chairman of the Central Military Commission, decided to use force, no matter consequences for China's international image. They were concerned that some of the People's Liberation Army troops, whose primary mission was to ensure the survival of the Communist Party, were reluctant to slaughter the students and civilians gathered in the square.

Of these events, only some before/after pictures were taken, due to the violence of the events. However, some restored footage recently emerged, showing the last minutes before the military attacked.

A canker for national memory and international relations

The number of victims is subject to debate, probably several hundred, and has never been published. The Tiananmen 'events', are officially presented by the Communist Party as an attempt to overthrow the regime, and it remains the main taboo in contemporary Chinese history.

They resulted in a double movement of acceleration of economic reforms at the beginning of the 1990s, intended to satisfy—successfully—the expectations of a very large part of the population encouraged to 'get rich' and, at the same time, to take political and ideological control. The re-legitimisation of power was based on impressive economic growth and a nationalist discourse of power based on revenge.

Economic successes have also allowed Beijing to drown the stigma of the Tiananmen massacre abroad after a limited period of isolation and sanctions. The last concrete legacy of which is the embargo on arms sales to China still in force in the European Union and the United States.

A largely unchanged leadership

Nationalist rhetoric and patriotic education and mobilisation campaigns are still relevant today, at the heart of China's territorial tensions with its neighbours. The arrival in power of Xi Jinping in 2012 did not call these choices into question. On the contrary, ideological control has been strengthened, and the nationalist discourse has been able to rely on constantly developing military capabilities. Since Tiananmen, the defence budget has increased by an average of 10% every year.

For the Chinese leaders of today as for those of yesterday, the fear remains the same, that of a change of regime or an irreversible evolution. But the inevitable tensions that China is experiencing, between economic openness and political closure, control of information and capacity for innovation, the absence of a legal system and the fight against corruption, have not been resolved and can only slow down the full emergence of Chinese power in a globalised world from which it cannot escape.

The State Machine... you think it will listen?