We often hear about the Mariana Trench, this surprising living laboratory in the Pacific Northwest that is considered the deepest marine trench known to date. It is followed in 10th place by its not-as-popular Atacama Trench, also known as the Peru-Chile Trench, with a depth measuring 8,065 meters. The team that embarked on an expedition mission here were fortunate enough to be able to film what could be three strange new species of the ‘snailfish’ family.

Discover our latest podcast

A mission into the globe’s depths

40 scientists of 17 different nationalities came together to form the team that underwent this expedition to explore this Hadal Zone. Considered one of the last great frontiers of marine biology, the Hadal Zone is located below the abyssal zone (around 2km to 6km deep), reaching depths of up to 11 kilometers. It has no less than 33 trenches, including the one we’re looking into today known as the Atacama trench.

In order to learn more about our ecology, researchers from Newcastle University developed various technological equipment that was adapted to these extreme and unknown environments. During their last exploration mission, the team was then able to capture more than 100 hours of video footage and almost 11,500 photographs, allowing some light to be shed on this obscure and dark world.

Three new species of fish

During this mission, the team came across three new species of fish between 6,500 and 7,500 meters deep. These fish seem to belong to the Liparidae or ‘snailfish’ family, which is a name that seems quite fitting due to their long, slimy, scale-free bodies with tiny fins under their rounded heads.

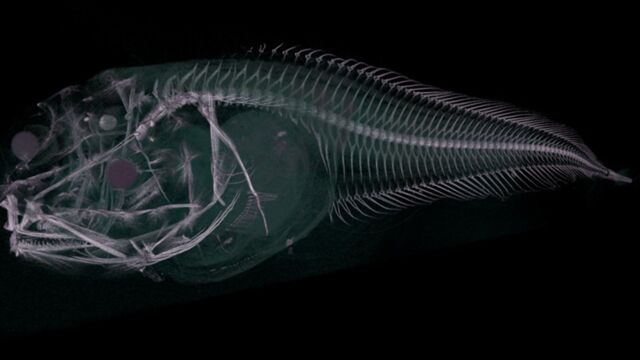

For now, the three species have temporarily been named ‘pink, blue and purple snailfish of Atacama’. In a video recorded by the team, we can distinctly see these ghostly-looking specimens interacting with the bait released by the researchers from their submarine next to a group of other creatures. A CT scan of one of these fish reveals that it has a complex and delicate skeletal architecture.

‘Their gelatinous structure means they are perfectly adapted to living at extreme pressure and in fact the hardest structures in their bodies are the bones in their inner ear which give them balance and their teeth. Without the extreme pressure and cold to support their bodies they are extremely fragile and melt rapidly when brought to the surface,’ says Dr. Thomas Linley who was a member of the expedition.

Acrobatic crustaceans

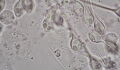

Among the team’s other discoveries are the surprisingly acrobatically talented isopods. Belonging to the Munnopsid family, these rare crustaceans have a small body attached to long legs. They are able to swim backwards and upside-down using paddles on their stomachs, before putting themselves back upright to be able to walk on the sea floor.

‘We don’t know what species of Munnopsid these are but it’s incredible to have caught them in action in their natural habitat – especially the flip they do as they switch from swimming to walking mode,’ says Linley. It is very clear that there is still a world in the abyss that has a lot more secrets and surprises to share.