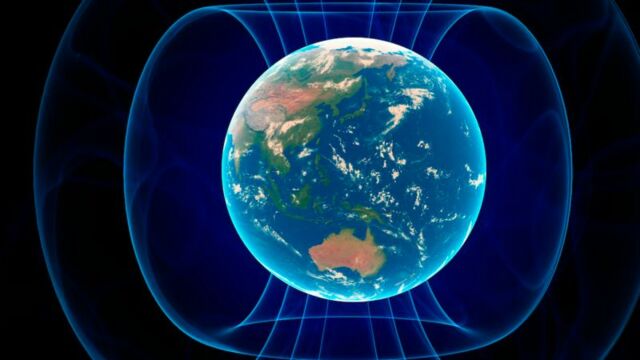

Unlike its geographic poles, the Earth's magnetic poles are actively moving. This is due to fluctuations in the molten iron at the heart of the planet, at the solid inner core, which affects the magnetic field. Thus, unlike its geographical counterpart, the North Magnetic Pole - indicated on all compasses by the letter N - is migrating towards Siberia (Russia). This is at such speeds that scientists are struggling to understand what is happening.

Discover our latest podcast

A movement never before observed

According to the National Centres for Environmental Information (NCEI) of the U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), the North Magnetic Pole has travelled approximately 1,398 miles since its official discovery in 1831. While this movement has generally been quite slow, allowing scientists to track its position, it has accelerated in recent decades to an average speed of 34 miles per year.

The most recent data suggest, however, that this movement towards Russia has slowed to about 25 miles per year. This is still unprecedented. 'The movement since the 1990s has been much faster than at any time in at least four centuries,' said Ciaran Beggan, a British Geological Survey specialist interviewed by the Financial Times. We really don't know very much about the changes that are driving it in the Earth's core.'

Every five years, a new predictive model is developed

Researchers cannot at this time fully explain the extreme unrest at the North Pole. What they can do is map the Earth's magnetic field, and calculate its rate of change over time. This representation is called the World Magnetic Model (WMM). It is used in GPS navigation tools, consumer compass applications, and systems used by NASA, the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA), and the military.

However, the foresight powers of the WMM are not set in stone. To maintain its accuracy, it must be updated every five years. 'WMM's prediction is very accurate as of its publication date and then deteriorates toward the end of the five-year period when it must be updated with revised values of the model coefficients,' noted NCEI. But this year's refresh occurred a year earlier than expected. WMM 2020 was released on December 10th because of the speed at which the North Magnetic Pole has drifted, and also to keep its valuable predictive model up to date.

A reversal of the poles

Although the current fluctuations are cause for concern, this is a moderate movement compared to what has already occurred in the Earth's history: movements of the magnetic poles so great that they tilt. This reversal of the polarity of the magnetic field, where the North Magnetic Pole is located at the geographic South Pole, would take place every 200,000 to 300,000 years. The last reversal took place 770,000 years ago.

But while some believe that reversals could occur during a human lifetime, the results of a study published in Science Advances last August do not support this theory. Researchers relied on the information contained in ocean sediments, Antarctic ice caps, and lava flows. These samples revealed how, over a million years, the Earth's magnetic field weakened, shifted, stabilised or reversed.

Time to adapt

Finally, the research team discovered that the last reversal of the Earth's magnetic field took 22,000 years - twice as long as expected. They also found that it was decreasing in intensity by about 5% each century. Signs of weakening indicate that the field is about to reverse. But it is difficult to know when this will happen.

If it does, it could have an impact on navigation, satellites, and communications. But researchers are reassuring that with the help of WMM, for example, we would have generations to adapt to long periods of instability in the Earth's magnetic field.