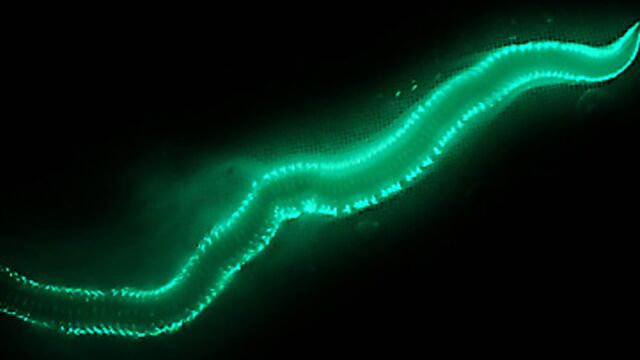

The saying goes that ‘all cats are grey in the dark.’ Cats maybe but this is certainly not the case with the ‘Bermuda fireworm,’ a polychaete worm from the Atlantic Ocean that, a few nights after a full moon, can be seen shining a thousand little lights in the evening. This fascinating spectacle created by creatures with such extraordinary powers are being studied in detail by researchers, which has been published in the PLOS One journal.

Discover our latest podcast

Their appearance in the Atlantic Ocean have fascinated humans for centuries. In 1492, Christopher Columbus himself recorded the strange phenomenon in his logbook on October 11th: ‘it looks like the flame of a small candle that alternately rises and falls,’ a poetic interpretation which is nonetheless a bit far from the scientific truth.

It is none other than Odontosyllis enopla which is responsible for this ocean blaze of light, otherwise rightly nicknamed the Bermuda fireworm. While it spends most of its life hidden in mucus tunnels in the marine sediment, the annelid begins the fireworks show during the mating season.

A dazzling encounter

As soon as the mating season arrives, the female Bermuda fireworm rises to the surface in order to dazzle any potential mates, as well as anyone lucky enough to witness the scene. The observation window for the show is quite narrow so one would have to be quite lucky indeed.

The spectacle occurs only once a month, two to five days after a full moon, and about 55 minutes after sunset. More intense in the summer and early autumn, the performance can be measured to the millimetre. ‘The female worms rise from the bottom and swim rapidly in small, tight circles while shining, which looks like a cluster of small azure stars across the surface of an intense black water,’ describes Mark Siddall, a zoologist specialising in invertebrates at the American Museum of Natural History.

More in depth scientifically speaking than the writings of Christopher Columbus, but no less poetic!

Aquatic shooting stars

After this introduction comes the climactic second act. ‘The males then head towards the light made by the females, and rise in a flash from the bottom of the ocean like comets; they are luminescent as well. A small explosion of light occurs when both pour their gametes into the water. This is by far the most beautiful demonstration I have ever witnessed,’ says Mark Siddall.

Returning to more pragmatic matters, despite this ambient show of magic, the researchers questioned this mechanism which allows the small worms to regulate the timing of their aquatic ballet with such precision. ‘It's as if they have a pocket watch,’ jokes one of the authors of the study, biologist Mercer R. Brugler of the American Museum of Natural History.

Despite some progress which has been made, the time management capability of the Bermuda fireworm is still puzzling. Scientists nevertheless speculate that the choice of a few days after the full moon is not due to chance. According to them, this period of time allows the worms to take full advantage of the total absence of nocturnal light, in order to increase the chances of the males detecting the bioluminescence of the females.

Bioluminescence with unique origins

Be that as it may, the mechanism at the origin of the emission of light by these unusual worms has been perfectly explained, following an unexpected discovery made by the researchers.

By studying the DNA of Bermuda fireworms, researchers were able to identify a specific enzyme, known as luciferase, which causes the animal's bioluminescence. This protein is also produced by many other living things such as fireflies, bacteria, small crustaceans and other copepods. Thus the only thing all these creatures have in common!

Scientists have indeed taken the precaution of comparing the luciferase of Bermuda fireworms with that of other organisms. The result was that the version held by the polychaetes is in no way comparable with that of other bioluminescent species.

‘It is particularly exciting to find a new [type] of luciferase, because if you can get things to light up in particular conditions, it could be really useful for labelling molecules in the [domain] of biomedical research,’ says biologist Michael Tessler, also affiliated with the American Museum of Natural History. The Bermuda fireworm is thus not only at the origin of an outstanding firework display, but also moonlights in the medical field!