Fears of needles, storage complexities and strained staff are just three problems that go hand-in-hand with run-of-the-mill needle vaccines. But, one new study has proposed a solution in the form of microneedle patches, otherwise known as intradermal vaccines.

Discover our latest podcast

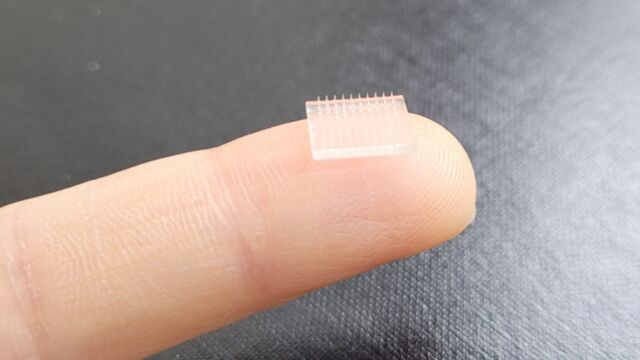

Researchers at Stanford University and the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill have taken it upon themselves to create a microneedle patch COVID vaccine that is no bigger than a 50p coin.

In the study, published in the Journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America (PNAS), the 3D-printed polymer patch already resulted in successful in vitro and animal trials. When tested on mice, the patches offered a 10-fold increase in immune response and a 50-fold more significant antibody and t-cell response than the standard jab.

Microneedle vaccines are a way to overcome standard vaccine obstacles

The study explained that microneedle vaccines could help overcome a myriad of problems that affect current COVID jabs. Microneedle patch vaccines can be stored for up to 30 days at room temperature, making them easier to transport and store than the standard vaccines that need to be kept refrigerated or frozen at specific temperatures.

Additionally, microneedle patch vaccines can be applied without the help of a healthcare professional, freeing up already stressed staff. Of course, the patches also mean that those with the all-to-common fear of needles will be more inclined to get immunised.

Lead study author Joseph M. DeSimone, a professor of chemical engineering at Stanford University, explained: ‘In developing this technology, we hope to set the foundation for even more rapid global development of vaccines, at lower doses, in a pain- and anxiety-free manner.'

How do microneedle patch vaccines work?

The microneedle patches used in the study were created using a CLIP prototype 3D printer that lead author Professor DeSimone designed. The benefit of the 3D printing process is that the microneedles can potentially be customised to target different viruses and diseases such as the flu, measles or COVID-19.

The main difference between microneedle patches and regular injections lies in the intradermal application. Typical needle vaccines penetrate the skin and inject into the muscle. However, microneedle patches will instead disperse the vaccine into the skin’s dermis, just underneath the outer layer of the skin known as the epidermis.

Researchers have pointed out that the shallower application of an intradermal vaccine could lead to better immune responses in humans as we have immune cells in our skin called antigen-presenting cells (APCs). So, vaccines that deliver into the skin allow the body to recognise and remember pathogens more effectively.

The patches are made from 100 biodegradable microneedles coated with DNA sequences that help generate an immune response. And, while DNA vaccines are easier to produce than mRNA vaccines like that of Pfizer and Moderna’s COVID jab, they often have more difficulty being taken in by a cell’s nucleus. But, the higher levels of APCs in the dermis give the DNA higher chances of entering the nucleus of the cells.

The microneedle patch vaccines still need to undergo human trials, but so far, the results seem promising.